Sharing The Nation

March 30, 2008 By ZAINAH ANWAR

Once Umno could put up a banana stump and it could win an election. Now the Opposition can put up a motley of bloggers, activists, petty traders and amateur videographers to stand for a seat and they can win.

EVERY domination bears within itself the seeds of its own destruction. The fall from power of once dominant political parties (and they can rise again), such as the LDP in Japan, the KMT in Taiwan, the Congress Party in India, and the PRI in Mexico, shows that the exercise of power by its very nature eventually leads to a process of disintegration of the ruling group.

The dictates of power alienate the dominant party’s electoral support base and create factions and frictions within itself that leads to its own decline.

That this finally happened to Barisan Nasional (BN) was a long time coming. The first writing on the wall emerged in 1987-1988 following the bruising leadership battle between Team A led by then Prime Minister Datuk Seri Dr Mahathir Mohamad and Team B in Umno, led by Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah and Musa Hitam.

Public disenchantment with the BN was set in place with the slide towards autocratic rule then. The leadership challenge laid to rest the promise of a “bersih, cekap, amanah” government that had swept the public imagination in the 1982 general election.

The deregistration and split in Umno, the sacking of the Lord President and five Supreme Court judges (three were eventually reinstated), the detention under ISA of over 100 political and civil society leaders under Operation Lalang, the closure of newspapers, the amendments to several laws to close the doors of judicial review – all set in motion the wave of disaffection with the BN leadership and its strong-arm rule.

These events entrenched a decided slide towards authoritarianism and the shrinking of the public space in Malaysian politics. The 1990 general elections saw PAS win over Kelantan, in alliance with Tengku Razaleigh’s breakaway Semangat 46, thus ending 12 years of BN rule that it has not been able to reverse.

But this was seen as only a hiccup by the political elite as new heights of economic success and wealth created by Dr Mahathir’s modernisation vision led to a new sense of well-being and confidence. This led to unprecedented popular support for the BN government in the 1995 general election.

All was forgiven or forgotten, for there was wealth, prosperity and stability to be enjoyed by everyone. Semangat 46 dissolved itself and its Umnoputras at heart joined the father party for a piece of the political and economic pie.

But the financial crisis and the sacking and mistreatment of Datuk Seri Anwar Ibrahim in 1998 changed the public mood once again. All the sins of the past were revisited. The electorate was poised to repudiate BN.

The party still won 77% of the parliamentary seats in the 1999 elections, but Umno suffered its worst ever result then, its seats declining from 94 to 72, while PAS emerged with the leadership of the Opposition, winning 27 seats. Two states fell to the Islamist party and the BN’s popular support declined by 10%.

In a long analysis of the election results, I identified the litany of disgruntlements that the Government could no longer sweep under the carpet.

There was palpable demand for greater transparency and accountability, independence of the judiciary, a free and responsible press, a more participatory and open political system, an end to police abuse and misuse of power, and an end to the intricate web of business and politics that bred cronyism and corruption and where big business always triumphed over community and environmental interests.

The message was clear then. The Malaysian electorate wanted to see change in the way this country was governed, how the law was applied, how politics was conducted and how business was run.

Umno and BN needed to go back to the drawing boards to reinvent themselves to respond to the changing demands and priorities of a well-educated, critical, politically conscious, Internet-savvy, upwardly mobile, younger generation of Malays and Malaysians.

But this process of renewal did not take place and the eventual denouement of a dominant party that refused to change was postponed for another electoral round. For when Dr Mahathir chose Datuk Seri Abdullah Ahmad Badawi as his successor, the electorate was swept by the new leader who promised to be the Prime Minister of all Malaysians, who promised to eliminate corruption and to introduce open tendering for government contracts and who regarded the NGOs as the eyes and ears of the government, instead of the pet poodles of the West as so derisively dismissed by the past administration.

When BN went to the polls in 2004, the new Prime Minister personified that change clamoured for by the electorate.

Those who voted for PAS and other opposition parties in 1999 returned to BN. A kinder, gentler Malaysia and a more open and democratic Malaysian politics were in store as the avuncular Pak Lah won public acclaim and led BN to its greatest electoral victory, winning 199 of 219 parliamentary seats.

So where did it all go wrong in those short four years?

Much has been written. While many of us shared in the Prime Minister’s vision of a democratising, transparent and accountable government and his promise of an inclusive rule for all Malaysians, his failure to deliver on much of this grand vision and his inability to take charge of his change agenda in the face of resistance from powerful centres of power within Umno and its BN partners, within the civil service, the police, and even within his own Cabinet, eventually led to a massive loss of confidence.

It was not supposed to be business as usual. But on the ground, it was much too much of the same thing.

Change, of course, takes time. But given the erupting series of issues of public concern, from snatched bodies to the Lingam tapes, from rising crime to rising prices, local development without public representation, political leaders behaving badly, and allegations of corruption and cronyism that did not abate, the electorate was in no mood to wait for the promised change to come or to even acknowledge that some change has indeed taken place.

As a Muslim democrat who believes in women’s rights and human rights, the turning point for me was the Umno general assembly of 2006. I wrote then of the barefaced racial and religious supremacist oratory at the general assembly that scared and alienated many Malaysians.

The reaction was immediate. I met people who were already planning to spoil their ballot papers or vote for the Opposition.

For many moderate Malaysians, that was the point when Umno crossed the line. A party that prided itself as the bedrock of centrist politics, that from its birth held an inherent belief in the politics of accommodation necessary for this divided multi-ethnic multi-religious society to survive, had presented an extremist face to Malaysians.

That fateful assembly was of course the culmination of over a year of demonising of moderate voices in Islam, of the Government ignoring the demands for respect for the rule of law and fundamental liberties guaranteed under the Federal Constitution, of the failure of the political, administrative and judicial authorities to uphold the law and deal with compassion and fairness the heart-wrenching cases of conversion and religious rights and freedom that saw families torn apart and ethnic minorities feeling assaulted by a seemingly hegemonic majority.

At the local level, my pro-establishment neighbourhood saw its green lungs disembowelled for a mini-Manhattan of skyscrapers, a hotel and shopping complex in the heart of Pusat Bandar Damansara (PBD).

A strip of green hill along Jalan Beringin, which was preserved as a green lung in the original development plan because of its steep gradient, was stripped bare to build multi-million dollar bungalows.

All protests by the community fell on deaf ears as the combined might of City Hall and greedy developers railroaded neighbourhood associations. A meeting at City Hall between the residents association and the developers was deliberately scheduled for the day after Christmas, without prior notice to the residents association.

Thus our voice went unheard, approvals were finalised, and the tree cutting and earthworks began almost immediately.

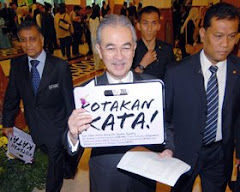

At a May protest rally against the intensive development in PBD, the Tan Sris, Datuks, and professionals of Damansara, many of whom were Umno, MCA and Gerakan members, were already talking of boycotting the elections or spoiling their ballot papers; many then could still not bring themselves to vote for the Opposition.

But the warning was clear. “Don’t turn us into your enemy,” one Umno member boomed at the rally.

The belief that the mighty BN could never fall because it controlled all levers of power, and the Opposition could never win because it was an unviable alternative, has bred an arrogance of power among many in Government that bordered on contempt for dissenting sentiment.

Many BN political leaders responded to protests and criticisms by taunting the electorate to vote them out if we did not like their policies; they contemptuously dismissed human rights and women’s rights activists by telling us that our voice and our issues did not matter to their constituents in the kampung. When it suited them they saw themselves only as jaguh kampung, conveniently ignoring the national agenda and the national mission.

Even as late as the campaign period, one Chief Minister dismissed the Hindraf rally and the issues raised as irrelevant to his constituency. They even dismissed the new media as irrelevant because their kampung folk don’t own computers and don’t read the Internet.

They were even blissfully ignorant of the power of the SMS as a medium of political persuasion. They had nothing to worry about, they thought, as they controlled radio, television and the mainstream newspapers. Little did they know that the electorate had switched off. Far more accurate results were coming through their SMS than anything any of the television stations could offer that March 8.

They thought they were the Masters of the Universe and therefore they had nothing to learn from anyone. How so out of touch they were.

While Opposition party politicians were busy making new friends and allies, learning about human rights, women’s rights, Islam and democracy, framing their message to capture public angst, updating their blogs, websites, facebook accounts, getting their message out, raising funds and mobilising the crowds through the Internet and SMS, many of the BN politicians remained smug in their imagined invincibility of incumbent power and money, and the roar of their SUVs.

How the tables have turned. Once Umno could put up a banana stump and it could win an election. Now the Opposition can put up a motley of bloggers, activists, petty traders and amateur videographers to stand for a seat and they can win.

Malaysians finally wanted their vote to make a difference.When leaders fail to lead, the rakyat will show them the way. The decline of a dominant party and the new era of more competitive multi-party politics bring much uncertainty, but with it the potential for the strengthening of Malaysian democracy.

If the Opposition does not get its act together, the protest vote of 2008 could remain just that, a protest. But should the Opposition show the political will to submerge its discordant ideologies and ambitions and merge into a genuine multi-ethnic democratic alternative and prove that it can govern well, and the BN has the courage and imagination to reinvent itself, then Malaysian democracy could possibly return to the original trajectory planned by its visionary founding fathers – that of a democratic, modern, pluralist, secular state that celebrates the strength of its diversity through a national life and politics that promotes co-existence and accommodation and eschews a winner-takes-all mentality.

That is the most optimistic outcome.

The jury is very much out on whether our political leaders, be they in the BN or the victorious Opposition alliance, have it in them to see clearly the path the rakyat have already taken.

Zainah Anwar is an activist on women’s issues and was the face of Sisters in Islam for two decades

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment